It is undeniable that technical testing of systems remains a key part of any organisation’s cyber security assurance activities. These technical, or ‘penetration’ (pen), tests also form the basis of several regulatory and compliance elements, making them a “must have” for all organisations. Given the number of advanced persistent threats (APTs) firms need to ward off, they are as essential as any other form of risk assessment.

As pen tests are such an important exercise, this is a subject worth considering and exploring in further detail. This is especially true now that firms in regulated industries are under increasing pressure to demonstrate operational resilience and robust cyber security (for example, the EU's Digital Operational Resilience Act [DORA]).

The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) defines pen testing as, “A method for gaining assurance in the security of an IT system by attempting to breach some or all of that system's security, using the same tools and techniques as an adversary might.”

The NCSC also says, with a sigh that is almost audible, that “in an ideal world” organisations “should know” what pen testers are going to find before they find it.

No script kiddies allowed

In fairness to most organisations, however, there is an unspoken truth in the cyber security industry that the largest penetration testing houses tend to conduct huge numbers of pen tests using a combination of very junior resources and flawed delivery methodologies, resulting in inconsistent outcomes.

Such a ‘commodity penetration test’ is an exercise that is, in most cases, conducted solely to provide evidence of a security-related activity having been conducted. In terms of replicating a threat actor, the comparison would be that of a ‘script kiddie’ – i.e., the lowest-skilled recognised category of threat actor. Ineffective or commodity penetration tests can have a significant impact on organisations, including but not limited to:

- A focus on quantity rather than quality of delivery, limiting senior resources from getting hands-on, and therefore lowering quality standards.

- Excessively high targets for testers, thereby limiting the ability of individuals to conduct their own research and stay on top of the most recent innovations in a constantly changing threat landscape. The conclusions drawn are therefore potentially out of date or simply incorrect.

- Tough scheduling requirements often mean that the job needs a greater range and number of resources to get it done within the limited timeframe. This in turn vastly diversifies the quality of the outputs and deliverables, making comparisons between years or functional areas difficult.

Nuances should be understood — small details can be the difference between a valuable exercise, and one that has (and should be recognised as having) limited value to an organisation. While saying this out loud may not be easy, it is an uncomfortable fact that many organisations and individuals should recognise.

The value of knowing your opponent

Our practitioners have first-hand experience of conducting incident response activities for organisations that have recently been penetration tested. These organisations are frequently confused (and bemused) as to how an external threat actor successfully breached them so soon after running these exercises. Typically, they are organisations that have not fully understood the importance of having an effective scoping exercise that considers the wider implications of conducting a pen test.

A truly effective penetration test is one that seeks to replicate the actions of cyber security threat actors of the highest calibre. It should be conducted against a backdrop that encourages behaviour, thinking, and actions that reflect that of a determined threat actor.

Certification bodies such as CREST have worked wonders in terms of standardising and increasing the baseline level of knowledge that an employee has when conducting penetration tests, but the objective reality is that, even with formal certifications, buyers of a penetration test may not receive the gold standard in services that they expect and demand.

Articulating the ‘so what?’

The true value of a penetration test lies in having someone examine and explore what could potentially interfere with, damage, or harm a network or technical environment. It is vital that your entire attack surface is tested; this can be achieved with an effective threat intelligence function that operationalises the insights from the wider threat landscape and embeds them into a client-facing penetration test.

This constant learning should be combined with experienced practitioners who have the scope and remit to explore the potential avenues for exploitation within the client environment, in the same way that an attacker could. Once issues or vulnerabilities are identified, the testers should be able to articulate the findings, and what it means for the business, and also know how to address the issues.

This is only possible when the client can interact directly with the technical testers. All too often, our team has seen intermediaries within organisations soften or misinterpret the findings and fail to articulate the vital “so what?” for clients.

Answering the question of “so what?” should be at the heart of an organisation’s considerations when it’s procuring a test. It does, however, require the individuals who commission the test to have a broader, holistic approach to something that has traditionally been seen as the sole prerogative of an isolated IT team.

A checklist for commissioning a penetration test

1. Identify and understand your own objectives for conducting the exercise:

- What are we trying to achieve by having a penetration test?

- Are we actively seeking to reduce risk?

2. Explore your own internal stakeholder reporting requirements:

- Who needs to see the report?

- Who has had access to past reports?

- Would executive leadership benefit from having a version of the report?

- Would our technical team benefit from interacting directly with the technical penetration testers?

3. Understand the delivery model that potential vendors use:

- Who will conduct the penetration test?

- Are there internal mechanisms within the organisation that ensure quality of delivery?

- What is the process for engaging with the testers? Is this standard practice?

- Is threat intelligence embedded in the process?

4. Recognise the limitations of potential delivery models and vendors:

- Are the individuals conducting the assessment accurately representing the methods of potential attackers?

- Do the penetration testers have enough time to collect sufficient information to provide coverage?

- Do the vendors have a model that ensures appropriate creative licence to the testers to explore any additional sources of risk?

5. Understand the deliverables and how the output aligns to internal processes and risk management:

- Does the report provide business context that can be understood and aligned to existing processes to help aid risk reduction?

- The deliverables must answer the questions, “what?,” “so what?,” and “now what?”

“Now what” is a question that requires exploration in-depth – which we will do in next week’s instalment of Cyber Series.

Cyber Risk

We bring the best of our collective experience, energy and creative power to fiercely safeguard our clients and fortify their communities.

Insights

Operational Due Diligence: A Playbook for Asset Owners and Allocators

Navigate the evolving ODD landscape, with industry insights that will help you to identify, assess, and monitor emerging risks.

Thomas Murray Risk Update: Middle East Developments – Impact on Post-Trade and Capital Markets

Thomas Murray’s Risk Committee (RC) met today to assess the rapidly evolving geopolitical situation in the Middle East.

Why 72 hours is the New Standard for M&A Cyber Due Diligence

A decade ago, cyber due diligence sat somewhere between “nice to have” and “we’ll deal with it post-close.” That world no longer exists.

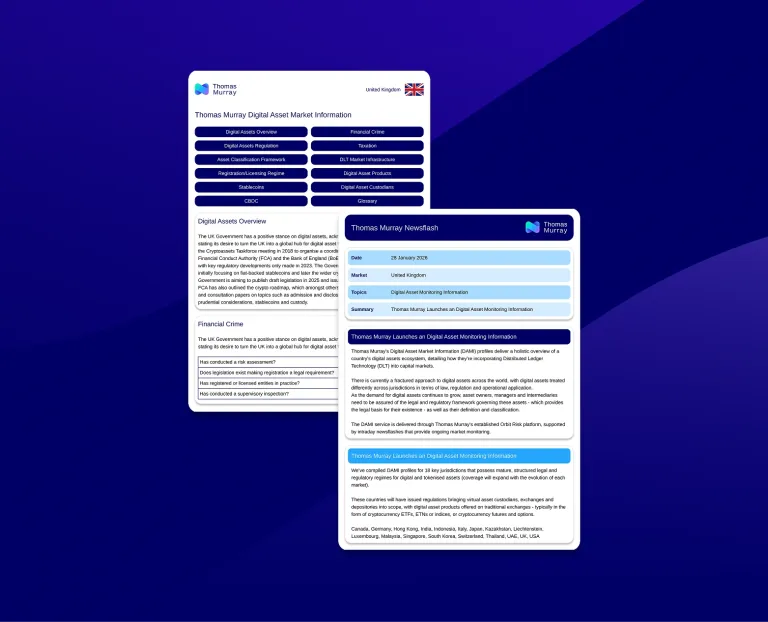

Thomas Murray Launches Digital Asset Market Information (DAMI)

Thomas Murray, a global leader in risk management, due diligence, and cybersecurity services, is proud to announce the launch of Digital Asset Market Information (DAMI).