External threats from threat actors such as ransomware-as-a-service groups like LockBit and Conti rightly get a lot of cyber security press. But for organisations there is also the real and ever-present threat from an insider. As we saw in Fighting a rising tide: Cyber crime and the water supply, insider threats to critical infrastructure are significant, though they are present in any organisation.

The UK’s National Protective Security Authority (NPSA) has identified insider threat as being of such concern that it has, for the first time, issued its own communication guidance on the topic. The guidance is part of the NPSA’s umbrella campaign, “Be Insider Risk Ready,” which launched in March 2024.

The NPSA’s own research indicates that current factors in the increased level of insider threat include:

- societal changes, such as the worldwide cost of living crisis;

- elevated geopolitical instability; and

- declining levels of trust in authority.

These factors sit alongside a global shift towards a more connected and mobile workforce. More people now work remotely, with access to sensitive information and critical computer systems while out of the direct view of colleagues and employers.

What is the difference between an insider threat and an insider risk?

Quite simply, everyone with legitimate access to your resources using authorised credentials poses an insider risk. This includes people who no longer should be able to access your resources but still can. They are risk because they can gain access. Network security measures are not designed to keep them out, so strong passwords and intrusion detection systems are no defence.

An insider threat, on the other hand, is someone who has authorised access to your organisation’s resources and either intends or is likely to cause it harm. Insider threats can come from external contractors, short-term employees and even highly-regarded team members of long service.

Insiders who unintentionally cause harm are generally categorised as ‘negligent’ or ‘mistaken.’ For example:

- they use the same password for everything or fall for a phishing attack (negligent); or

- they send the wrong attachment to the wrong person (mistaken).

Although the term ‘insider threat’ implies malice. However, it's most often negligent insiders behind the largest number of incidents and who do the most damage, according to the US Ponemon Institute’s 2023 Cost of Insider Risks Global Report.

Combined, incidents caused by those who were negligent, mistaken or outsmarted cost an average of almost US$1.2m – more than the average cost of incidents caused by those motivated by malice or criminal intent, at ‘only’ US$701,500. Research from Carnegie Mellon University ranks the top malicious insider threat scenarios as:

1. intellectual property theft;

2. information technology sabotage; and

3. fraud.

Spotting the signs of determined, clearly intentioned insider threats – and heading them off – is therefore much easier than trying to detect who in your organisation is most likely to leave their laptop unattended on a train.

The security analyst who went to the dark side

A threat group targeted parts of Oxford Biomedica’s technical infrastructure in February 2018. In an email to Oxford Biomedica, the group issued a ransom demand of £300,000, to be paid in Bitcoin.

Ashley Liles, a security analyst with Oxford Biomedica, worked alongside colleagues and police to investigate and mitigate the incident. But he soon took a direct, and unauthorised, role in handling communications to and from the threat actor.

An investigation by the South East Regional Organised Crime Unit (SEROCU) identified Liles as being responsible for:

- accessing the private emails of an Oxford Biomedica board member more than 300 times;

- altering the original ransom demand; and

- changing the address of the Bitcoin wallet that the ransom was to be paid into.

Liles also created a nearly identical email address to the one used by the threat actor, which he used in his own efforts to pressure Oxford Biomedica into paying the ransom. The unauthorised access to the board member’s emails was traced to Liles’ home address. Though he attempted to wipe his devices only a few days before his arrest, SEROCU was able to recover direct evidence of his actions.

In July 2023, Liles pleaded guilty and was sentenced to almost four years in prison.

This incident incorporates all the hallmarks of an insider threat and highlights three key markers for threat detection.

Firstly, the insider took advantage of a stressful event for the business, likely hoping this would shield them from suspicion. Secondly, they used their privileged access to parts of the system to facilitate their offence. Finally, they took elaborate steps in an attempt to hide their tracks.

An insider doesn’t need to be privileged

Even an employee with only the minimum of access to client data can become an insider threat.

During the peak of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, thousands of people were sent to work from home with a moment’s notice. Among them was Karl Yates, who worked for the insurance company Royal Sun Alliance (RSA).

Soon after the first UK lockdown began, RSA started fielding numerous complaints from its customers. The customers were getting cold calls from various claims management companies that were trying to push them into making personal injury and damage claims. What drove these customers to complain to RSA was that the cold callers were using personal details that could only have come from RSA.

RSA’s investigation found that Yates had been accessing customer records without authorisation. RSA suspected him of stealing (exfiltrating) and selling this sensitive data. The company called in the Insurance Fraud Enforcement Department (IFED) of the City of London Police.

When IFED went to arrest Yates, next to his open work laptop it found his handwritten notes of details for customer accounts he had recently accessed. It also found more than 100 images of typed-up pages of customer details on his mobile phone.

This low-tech approach to exfiltrating customer data is difficult to detect in a remote working environment. However, it’s likely that correlating the customer complaints with accurate audit logs of what data had been accessed, when, and by who, helped RSA to identify Yates.

Industrial espionage in the AI world

It’s not just money and customer records that insider threats might be after. The latest technological advances are always highly sought after, and the way in which technology giants are supporting the adoption of AI, unsurprisingly, makes them a target.

Early in March 2024, the US Department of Justice revealed an indictment naming former Google employee Linwei Ding. During his employment with Google, Ding is alleged to have exfiltrated confidential Google intellectual property relating to its:

- data centres;

- hardware infrastructure;

- and the software platform used to support AI models and applications.

The indictment suggests that Ding initially avoided detection by copying data from these conditional documents to Apple Notes, before converting those into PDFs and uploading them to his own Google Drive account.

Ding is accused of industrial espionage. Shortly after Ding started saving Google’s data in his personal account, a Chinese AI startup offered him the role of Chief Technology Officer. Ding reportedly played a key part in raising capital for the startup via investor meetings in China.

On one of his trips to China, in December 2023, Ding uploaded more documents to a Google Drive account. This time, Google detected the activity. An investigation failed to find concrete evidence of wrongdoing.

Ding told the investigator that he had only uploaded the documents as a record of his work. He signed a statement confirming he had deleted, “any non-public information originating from my job at Google.”

A few days after the investigation wrapped up, Ding resigned. Suspicious of the timing, Google looked harder at his activities and uncovered his links to the Chinese AI startup. Google involved the FBI. Ding was arrested in March 2024 on four charges of theft of trade secrets.

This is a classic example of an insider threat; alleged theft of highly prized intellectual property, presumably for financial gain. Given the novel method Ding used, even Google, with its vast resources, may have missed the exfiltration of its sensitive documents had Ding not had his moment of carelessness while he was on the road.

An expensive AI mistake

The rise in sophisticated phishing attempts by threat actors has caused a corresponding rise in instances of negligent insiders.

In early 2024, a finance worker in Hong Kong with a multinational firm willingly handed over US$25m to fraudsters. The employee had initially been suspicious of the message from the Chief Financial Officer, asking for a “secret transaction.” However, when the external threat actor joined a video conference call posing as the CFO, the employee put those concerns to one side.

The threat actors are believed to have used deepfake technology to modify publicly available footage to convince the finance worker that everyone on the call was who they said they were. The fraud was only discovered when the worker checked directly with the company’s head office.

Insider threats aren’t just those with a drive to cause harm. They can also stem from those who think they’re doing the right thing and genuinely don’t foresee the harm their actions could cause.

What do these stories tell us? And what can be done?

Each of these stories are different in their complexity, their targets, and their levels of sophistication – but they all have a few things in common.

Firstly, an existing employee used their access (whether authorised at the time or not) either for their own personal gain, or for someone else’s. There was no need to make use of complex or malicious software or vulnerabilities, and in the case of the RSA breach just simple pen and paper was sufficient.

Secondly, on each occasion, and although their first action was not immediately picked up, the existence of monitoring or audit data aided the organisations in detecting and responding to the incidents. While the losses were real, it was still possible to understand how they happened. And although some interesting techniques were used to exfiltrate data or facilitate harm, ultimately the organisations had access to records that were complete enough to identify a person of interest.

Finally, each organisation was able to understand and quantify the risks that the actions that each of these insiders posed and took action to investigate and mitigate the impact. This was true even when years had passed and even when the insider’s actions had not been overtly malicious.

To detect and respond to insider threats, organisations have several options, including:

- Understand where your sensitive and confidential data is: Undertake a systematic review of all your organisation’s data locations and understand what they hold, how it is accessed, and how sensitive it is to your business operations.

- Implement robust monitoring: Once you understand where your data is, work out how you can monitor access to it. Data loss prevention solutions can give insight into the movement of data and alert security teams to suspicious activity. Monitoring shouldn’t only be technical; ensure robust policies and procedures are in place to control access to, for example, mobile devices and writing materials in places where especially sensitive data is handled.

- Monitor systems as well as data: Data will typically reside on a system or application, so the next step is to monitor those systems and be sure you can answer questions around data access to a satisfactory level. Investing in specialist software can be one solution, but ensuring you take full advantage of current products can be a great first step.

- Train your employees: Insider threats are not just presented by those with malicious intent, but also through a well-meaning employee’s mistake or carelessness. Train your people on the latest threats and ensure robust processes are in place to verify the identities of those carrying out key actions.

- Know how to handle the incident: Develop incident response playbooks specifically targeted to address your threats as a business and how an insider threat might occur. Once you’ve developed these, ensure you test them through tabletop exercises to ensure that every person involved in the response knows their role and responsibilities.

- Have experts on hand: An insider threat investigation can span multiple systems and data sources, so requires a methodical and defensible approach. Ensure that you have access to experts in digital forensics and incident response, and who have experience of presenting evidence in a legal setting should you need to take further action because of an insider threat.

Cyber Risk

We bring the best of our collective experience, energy and creative power to fiercely safeguard our clients and fortify their communities.

Insights

Operational Due Diligence: A Playbook for Asset Owners and Allocators

Navigate the evolving ODD landscape, with industry insights that will help you to identify, assess, and monitor emerging risks.

Thomas Murray Risk Update: Middle East Developments – Impact on Post-Trade and Capital Markets

Thomas Murray’s Risk Committee (RC) met today to assess the rapidly evolving geopolitical situation in the Middle East.

Why 72 hours is the New Standard for M&A Cyber Due Diligence

A decade ago, cyber due diligence sat somewhere between “nice to have” and “we’ll deal with it post-close.” That world no longer exists.

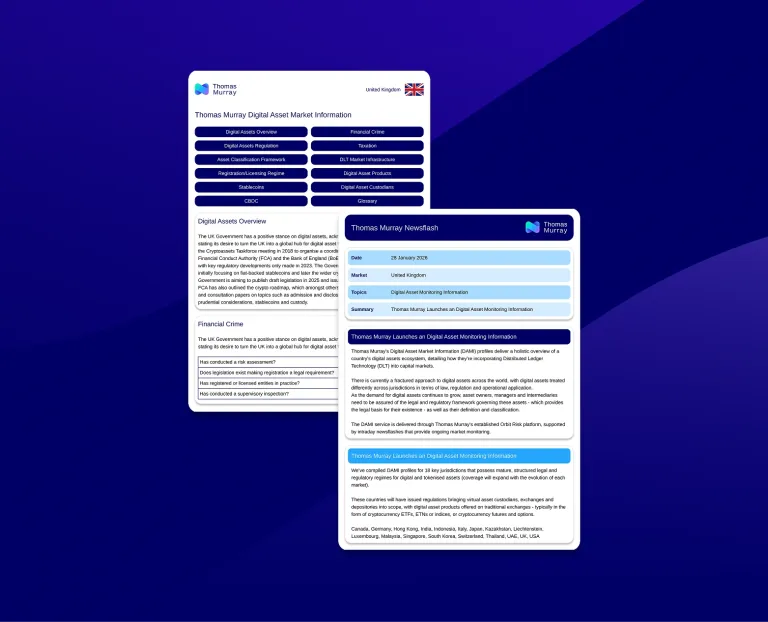

Thomas Murray Launches Digital Asset Market Information (DAMI)

Thomas Murray, a global leader in risk management, due diligence, and cybersecurity services, is proud to announce the launch of Digital Asset Market Information (DAMI).