Our Risk Solutions

Fund Services

We provide expert advisory services for custody, investment operations and strategy, as well as a powerful solution for Operational Due Diligence (ODD), third party risk and compliance.

Capital Markets

The world’s leading global advisory practice for financial market infrastructures since 1994, supporting FMIs to manage risk, regulation and market transformation.

Bank Network Management

The only comprehensive solution for Bank Network Management, supporting most of the world’s largest banks manage their complex global networks, local market exposures and compliance requirements.

Third Party Risk Management

Automate, accelerate and centralise third party risk management across your critical service providers and other relationships with our market-leading solution.

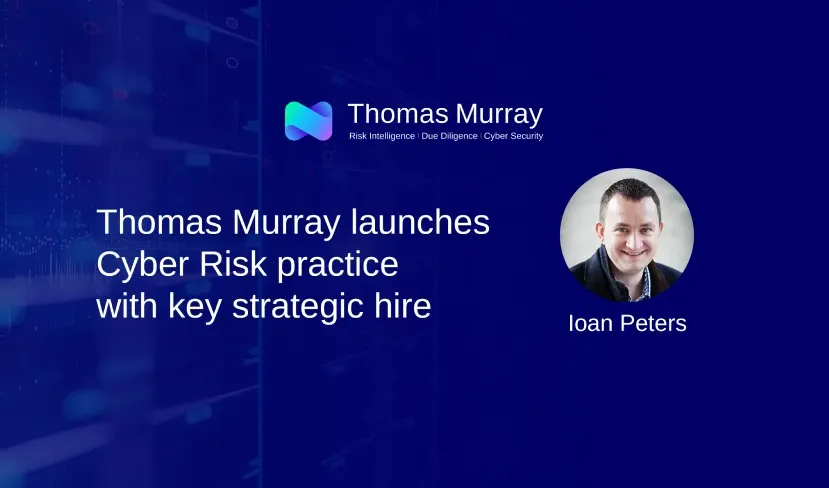

Cyber Risk

We bring the best of our collective experience, energy and creative power to fiercely safeguard our clients and fortify their communities.

Have any questions?

Orbit Risk

A suite of integrated risk, security, and due diligence tools. The solution for businesses who rely on global third parties to deliver essential support and services.

Orbit Intelligence

Centralise your monitoring and reporting, access Thomas Murray risk assessments and third party data feeds.

Orbit Diligence

Automate your DDQ and RFI processes for a wide range of use cases, accessing a library of off-the-shelf questionnaires and risk frameworks.

Orbit Security

Security ratings for enhanced attack surface management and third party risk. Monitor for breaches and vulnerabilities that could be exploited by threat actors.

Awards

Awards and recognition for Thomas Murray’s leading solutions.